Trade-offs: Natural and Contingent

What patents can tell us about trade-offs

Trade-offs are key to economic analysis, but not all trade-offs are the same. Trade-offs can be classified as:

Natural: those that cannot be avoided; or

Contingent: that they exist, but only under particular legal, political, and/or social structures.

To demonstrate, let’s look at the consideration of pharmaceuticals in Bhattacharya et al’s ‘Health Economics’.

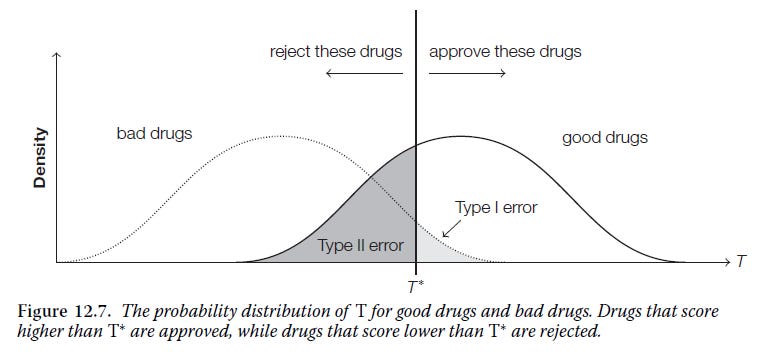

Firstly, we have the drug approval process. As this process is imperfect and costly in both time and resources, regulators have to contend with a trade-off between Type 1 errors, false positives, and Type 2 errors, false negatives. A stricter process will likely delay good drugs from reaching people in need, or even rejecting good drugs, while a more lax process will inevitably mean some bad drugs are approved. Such a trade-off is inherent to imperfect information, and would exist under any social structure.

Secondly, consider the trade-off of drug patents. Patents are effectively a temporary monopoly, incentivising the production of new pharmaceuticals by allowing firms to charge monopoly prices for their inventions over a period of time. The trade-off then faced is between current consumer welfare, who will pay higher prices (or even be priced out), and incentives for innovation.

However, there is nothing ‘natural’ about such a trade-off, the trade-off is contingent. It reflects the policy choice to fund innovation via a patent system. We may believe that this is the most effective method to encourage innovation, but it nonetheless reflects a choice. There are alternative methods which can be used to incentivise innovation, and each has their own contingent trade-offs.

Stiglitz and Greenwald (2014) for instance consider the following trade-offs as applying to patents and government funded R&D.

“The patent system (in principle) attempts to balance out the dynamic gains with the short-run costs of the underutilization of knowledge and imperfections of market competition… when the government finances research and disseminates it freely, there is still a static distortion (from the distortionary imposition of taxes), but no distortion in the dissemination and use of knowledge.”

So, when analysing a trade-off, it is worth considering to what extent it is contingent. Are there other overall frameworks that would better deal with this issue? A fixation on a particular contingent trade-off can miss the forest for the trees. There will always be trade-offs, but some trade-offs are more unavoidable than others.