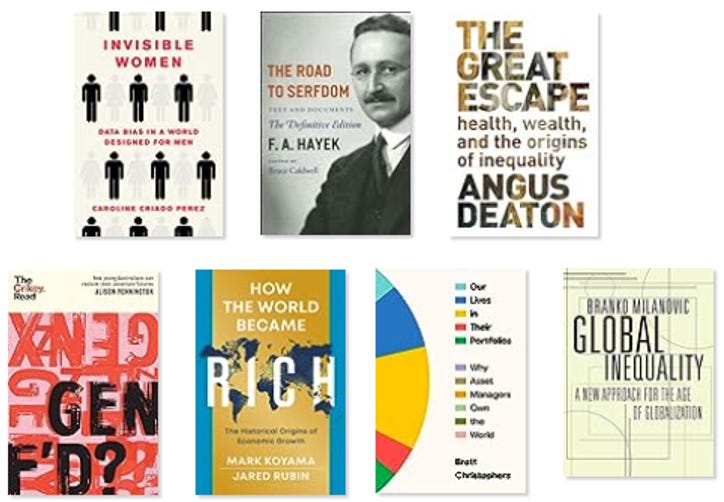

January 2024 in Books

Some brief thoughts

This is the first instalment in what will hopefully be a recurring series: books I’ve read each month, and my general thoughts on them. I may also start longer reviews depending on if I have capacity.

Books will be rated on a scale of: Excellent, Great, Good, Fine, Bad.

Some of the comments are likely to be longer than others, but that’s not an indication of quality, rather its usually dependent on how long ago I read it and whether I took notes.

The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality – Angus Deaton -

Excellent

This book is excellent, a wonderful example of a leading economist writing about what they know, in Deaton’s case: health, poverty and welfare. Broadly covers development in these areas over 250 years. Would recommend this book particularly for getting to know broad historical trends, such as the movement of preventable deaths from infants to the elderly, and his discussion of economic debates, including the Easterlin Paradox.

The work is weakest in the final chapter, where Deaton suggests that foreign aid does not help developing countries and likely hinders them, due to its ability to undermine accountable institutions. He has useful insights, such as critiquing what he calls the “hydraulic” approach to foreign aid, whereby one assumes that if dollars go in one end, outcomes must come out the other. The political economy argument against aid is however too strong in my opinion, given the unavoidable uncertainty in this area.

The Road to Serfdom – Friedrich von Hayek – Fine

This work can be broken down into roughly 4 broad themes, of varying quality:

· Critique of central planning: well written and insightful.

· Individualism vs collectivism: somewhat interesting, though inadequately presents the issues involved.

· Theory of how planning can turn a democracy into dictatorship: a slippery slope argument which subsequent history has not borne out.

· An intellectual history of socialism and fascism: highly partisan and bad scholarship, the worst sections of the book.

The most useful insights, concerning the information gathering role of markets, are better and more concisely presented in his The Use of Knowledge in Society, and similar themes are further elaborated in Seeing Like A State by James C Scott. Because of this, I do not think the work holds up today, and is primarily useful as a historical document. If you are going to read it, the ‘Definitive Edition’ is excellent, combining the work with related materials. If people are interested, I may write a longer review for the book’s 80th anniversary.

Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men - Caroline Criado Pérez – Great

Pérez’s classic on the data gap for women is insightful and engagingly written. It’s broad in coverage, reflecting on topics ranging from snowploughing to product safety. My personal favourite sections were on the workplace, childcare and retirement, probably because they’re welfare state related.

It’s worth noting that the book can be difficult to read in long stretches, as the volume of data presented can become overwhelming. For this reason, you should remember to note down key statistics you’re interested in, as they can be forgotten given 100 other stats.

How the World Became Rich: The Historical Origins of Economic Growth – Jared Rubin and Mark Koyama – Good

A good read, this book provides a broad overview of the debates surrounding economic development, providing useful summaries of the diverging views in the area. If you haven’t engaged with the literature before it would be a great place to start, particularly if you use it as a springboard to engage with the sources discussed. I would likely have rated this book as Great if I hadn’t read much in development econ before, but if you have already, it can be a little dry and I’d suggest Thirlwall and Pacheco-López’s Economics of Development: Theory and Evidence for a deeper, and more technical analysis.

Gen F'd?: How Young Australians Can Take Back Their Stolen Futures – Alison Pennington – Great

A compellingly written critique of Australia’s economic policies, and how they can be changed. I particularly enjoyed Pennington’s description of unions, and the ways in which unions based on rank and file mobilisation are distinctive to those that are more similar to an ‘arms-length insurance product’. I do wish the work had dug deeper into the specifics of Australia’s Industrial Relations regime, however the book is written accessibly for a popular audience, rather than economists/lawyers like myself.

Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization – Branko Milanović – Excellent

Milanović is a favourite economist of mine and this book was worth reading for a second time. As is common in his work, the book weaves a deep understanding of the economics of inequality with politics, history and ideology. The book describes inequality as taking place in ‘Kuznets Waves’ rather than a unidirectional process. If you enjoy this work, would recommend his Capitalism, Alone which builds more on the political economy arguments.

Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World – Brett Christophers – Great

Having greatly enjoyed Christophers’ Rentier Capitalism I approached this book with high expectations. The book is great, though not quite as good as Rentier Capitalism, focusing on the role of asset managers in contemporary capitalism (which he calls ‘asset manager society’). It is an engaging analysis, running through how asset managers became so dominant, the structure of such organisations, and its implications. To his credit Chrisophers avoids the trap of romanticising small capital, mum and dad landlords etc, providing coherent reasons as to why asset manager society is different to previous modes of capitalism, and the risks involved.