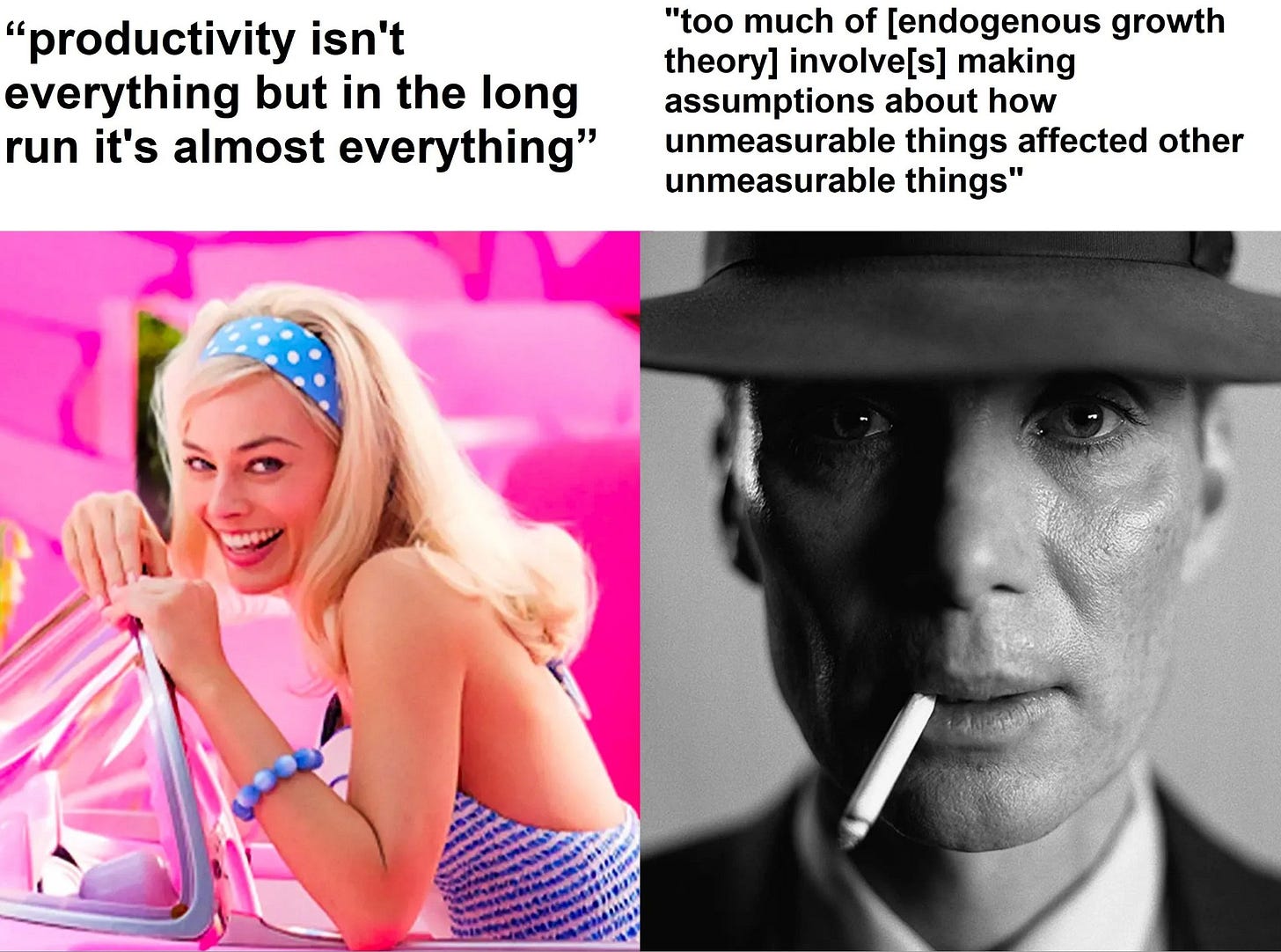

A Tale of Two Krugmans

The trouble with productivity discourse

“Productivity isn't everything, but in the long run, it's almost everything.”

This Krugman quote has proven so popular with economists it’s almost become a mantra, to repeat every time one discusses productivity or living standards. There’s good reason for this, productivity is important, extremely so.

Productivity discourse however suffers from a problem. While it is important, it is also famously difficult to reliably increase. While modern growth theorists can often agree on very basic prerequisites to economic growth: rule of law, basic education etc, how to bring it about in a modern rich economy is highly fraught. There is general acceptance of a global productivity slowdown, but not on its causes and how if possible, it is to be reversed.

This brings us to the second Krugman quote, this time on the endogenous growth model, which seeks to model technological change:

“too much of [endogenous growth theory] involved making assumptions about how unmeasurable things affected other unmeasurable things.”

The comment is not without merit. The famous Romer model includes variables for new ideas and their originality. The model is useful, but the measurement problems means it hardly provides guidance on concrete policies to spur growth. Further the Schumpeterian aspects of the model suggest that sometimes monopoly power is good, and sometimes it is bad, adding further complexity to our models of perfect competition.

The problem with productivity discourse is then not that productivity is bad. Almost nobody objects to producing more with less. The issue is that increasing productivity possesses two attributes, it is both very important, and hard to reliably increase. This is a dangerous place to be. In leu of strong evidence either way, it is incredibly tempting to suggest whatever policies you already preferred and label them as “productivity promoting”. The argument often resembles a motte and bailey, the author beginning their argument with the “productivity is important” statement, listing their preferred policies as “methods to improve productivity”, and then retreating to the “productivity is important” point when the merits of these policies are questioned.

In sum, one should be highly suspect in assessing someone's suite of policies to improve productivity growth: how are we measuring outcomes? Is this a level or rate effect? Are we assuming we'll overcome the global slowdown? Are among the first questions one should ask for these programs.

I think productivity is very hard to increase with economic tools. But I also think productivity is very easy to increase. My productivity increased massively by changes precipitated by covid.

Not only did I save 3 hours travelling each week. Not only did I get an environment for uninterrupted work for significant periods during the week. I also got vastly better tools to work with colleagues in other geographies.

There have been many other massive increases in my productivity over the last decade, none of which were about technology, or capital investment, and all or which were about breaking down institutional barriers to productive work.

Now managers are trying to decrease productivity again with back to the office mandates etc., even where objective measure of output have increased massively. The discussion is not about how to leverage the potential increased productivity made possible by saving transport time etc. The discussion is about how to make workers do what managers want, whether it makes sense or not.

It is sometimes discussed how teachers spend many hours, beyond face to face time, satisfying the demands of managers trying to control them. This is about reducing productivity, so that managers can have more power over workers.

One don't want to claim there is only one way to increase productivity. I think there are vast numbers of effective and simple ways to increase productivity. But giving agency and control to workers is one theme here.